Gertrude Bacon and the balloon that wouldn’t come down

One of the dangers of ballooning in England is that you’re never very far from the coast. If you’re above the clouds and the wind is right, you might be swept out over the sea if you stay up too long. Then you’re in deep trouble.

That possibility was on Gertrude Bacon’s mind in the early morning hours of November 16, 1899, as she and her father and another man floated helplessly over England.

Rev. John Mackenzie Bacon was a well-known aeronaut. When he heard that astronomers were predicting a great meteor shower for the night of the 16th, he had an idea. He knew there was a good chance that the skies would be overcast that night, so he convinced the Times of London to sponsor a balloon flight to report on the meteors from above the clouds.

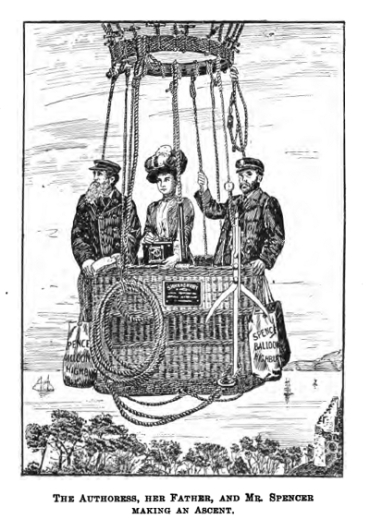

At four a.m. on the 16th, Bacon, his twenty-five-year-old daughter Gertrude, and a man named Stanley Spencer boarded the balloon.

The original plan had been to ascend the night before, in case the meteors came early. For that reason, the balloon was built without the usual “butterfly valve” at the top. Instead, it had only a “ripping valve.” This would have an important consequence during the flight, so it’s worth explaining the difference.

A butterfly valve was little more than a trap door at the top of the balloon that was opened by pulling a rope. It would snap shut when you released the rope. It was used to let off hydrogen if the balloon went too high, or when you wanted to come down. Butterfly valves were easy to open and close, but they tended to leak—not a good thing if you wanted to keep a balloon inflated for several days and possibly multiple flights.

So they built it only with a ripping panel, which is exactly what it sounds like: you pull the rope and it rips the balloon open. It was only meant to be used after the balloon came down and you were finished flying and wanted to let the hydrogen out quickly.

This meant that they had no way to bring the balloon down. They figured that with normal leakage, it would come down on its own after a few hours.

They were right about the weather. The clouds were thick that night. Nobody in England would get to see the great meteor shower. Nobody on the ground, anyway.

They launched from Newbury at 4 a.m. The coast at Bristol was sixty miles away. “Putting the force of the wind at thirty miles an hour, our voyage should last but a couple of hours,” Gertrude wrote. “Probably the speed was less, so three hours might perhaps be risked; but four would be very unsafe, and anything beyond quite out of the question. In the practically certain event of losing all sight of the earth above the clouds, we finally decided to finish our voyage at dawn, when our work would be at an end; though should the wind bear us northward, and the clouds breaking allow us to see our course, we might be tempted to keep up a little longer.”

Her father had promised friends that he would send a telegram as soon as they landed. But hours passed with no word. People grew worried.

Above the clouds, the meteor shower was kind of a bust, but the three aeronauts enjoyed themselves… at first, anyway. The following is from Gertrude’s account of the trip from her 1907 book, The Record of an Aeronaut: Being the Life of John M. Bacon, starting on p. 260:

We were a supremely happy party up there in fairyland, wrapped in rugs, nibbling dry sandwiches, counting stray meteors, and trying to judge from the occasional sounds of earth that reached us our probable landing-place. A chorus of wild barkings early in the voyage revealed we were over the kennels of Ashdown. The rumble of a train and the rhythmic clatter of horses’ hoofs stood for the G.W.R. and the Bath Road. As six o’clock approached we caught the buzzing of a steam hooter, and imagined ourselves somewhere in the vicinity of the Westbury iron-works. A church clock below tolled out the hour, and almost on the moment one of us, facing eastward, uttered an exclamation, and, turning, we beheld in the already fast-lightening sky the breaking flush of dawn. With great rapidity the daylight strengthened; and as it invaded the realm over which the moon had lately held sole sway the white ocean turned green and copper and golden, the stars faded, and thick grey mists swept upwards to hide the face of the conquered satellite as she sank, vanquished, towards the west. Then from below, as in a paean of victory, came up a chorus of piercing cockcrows, shrill, continuous, and triumphant. Seemingly there were many poultry farms below; and since the cocks aroused the dogs, and the dogs in turn woke up the cows, the rural cantata was loud and varied.

The grey mists were sweeping around our basket too, and stretching up clammy arms to clasp us. Surely our descent must be near at hand, and an easy landing in the still dawn assured. Yet a glance at the aneroids [barometers, used by balloonists to measure their altitude] revealed the astonishing fact that our height was unchanged, though no further ballast had now been thrown out for an hour and more. Also, as it grew lighter and lighter, the mist wreaths rolled up lower and less frequently around us, as if they lacked the power to enfold us in their damp embrace. An awkward silence had fallen on our trio, and Mr. Spencer’s genial face looked strangely white in the dawn. Presently the situation began to dawn on me. “Would it be safe,” I inquired, “supposing in another half-hour we are at the same height, to pull the valve open ?” Quickly and emphatically the answer came, “No !” and then I understood. In another half hour the sun would have risen, and with bright beams be drying the silk and expanding the gas, in which case should we not rise instead of fall, and rise for how long?

The next half-hour passed almost in silence; but the changing beauty of the dawn had lost its charm. Mr. Spencer continually threw out of the car tiny scraps of paper which fluttered ominously downwards. Bacon leant far out looking at the cloud floor, and in so doing his cap dropped overboard and disappeared instantly in the mist. Then indeed we laughed, for we pictured the scene below, saw in imagination the unsophisticated rustic going to milk in the early dawn, and fancied his face as, from the cloudy, overcast sky above, there falls at his feet—coming from heaven as it were—an ancient cap ! After this, above the sinking mists there shot up a brilliant ray of light, obscured for a moment, but rising again higher and higher; and as we gazed, fascinated, we saw the dazzling body of the sun in golden splendour mount majestically into his kingdom. Below us the creeping vapours, like baffled spirits of the night, sank down for the last time. Above us was the cloudless blue and the gaudy seams of the balloon, stretched tight and dry in the warming beams. Beside us, slung under the extinguished Davy lamp, the aneroids indicated a rise of 500 feet.

It was no use pretending any longer. We were cornered—caught in a trap. The sun would continue to increase in power and warmth; our balloon would continue to rise into realms where no clouds could form to shield us. It was now seven o’clock, and not for five long hours, till noon was past, could we even hope to descend. Five more hours in the narrow world in which we had already spent nearly three, was not in itself a terrible fate. There were plenty of dry sandwiches left in the packet, although certainly the contents of one of the ballast bags had become somewhat mixed up with them, and made them sand-wiches in literal truth. The bright sunbeams would ensure our being warm enough, November though it was. Our limbs were growing cramped in our little basket (six feet long, by three and a half wide and three deep) but not unendurably so. No, it was not here that our trouble lay, but in the awful uncertainty of our position, our inability to see the earth and so to judge in any way our direction or speed, our knowledge that we had already exceeded the time we had considered safe to be aloft when we left the ground, and our hopeless conviction that we were already close approaching the Atlantic, out over which we must surely float, hour after hour, beyond hope of rescue, until, with declining day, our spent balloon sank down far out on that watery waste, to rise no more.

For the time indeed we were over the country, and clearly travelling at a very slow rate. For almost half an hour we hung above one particular farm, and were able distinctly to recognize and distinguish the voices of its varied and vociferous live stock. But we were rising rapidly, 600 feet at least each quarter of an hour, and earth’s peaceful voices melted one by one into the silence of space. Soon beneath us the white snow-sheet of the cloud floor lay fiat and glistening a whole mile distant. To our lofty eyrie only the whistle and rumble of trains seemed able to penetrate; and yet, all too soon, there rose another softer sound, that confirmed our worst fears and sent the blood rushing to our hearts as with one accord we exclaimed to each other, “We are over the sea!” The sound was the shrill, well-remembered shriek of a ship’s steam siren, and mingled with it was the clash and clang of hammers in a dockyard seaport town. But more ominous far than these was that gentle rhythmic beat, that softly sighing accompaniment that could belong to one thing and one thing only in all the world. Who that has ever heard its distant murmur can mistake the sound of breaking waves upon a pebbly beach?

So our fears were realized, and we had reached the Atlantic at last. Now there remained but a few hours dragging, weary wait before our journey ended in the waves. Probably our balloon would float awhile on the waters, but we had no life-belts, and heavy net and cordage would entangle and hold us down. It was small odds indeed, on that wide ocean, that we fell within sight or aid of a ship. In very truth our case was desperate, and Mr. Spencer was in favour of ripping open the valve—put his hand, in fact, upon the valve-rope. There was the feeble chance, even then, that if in the awful descent that would ensue we threw everything out of the car, down to our own hats and coats, the empty silk, collapsing into a parachute, might bring us down alive. But Bacon restrained him. The risk was too terrible to contemplate. It was a choice of evils indeed, but drowning seemed a preferable death to being dashed to pieces.

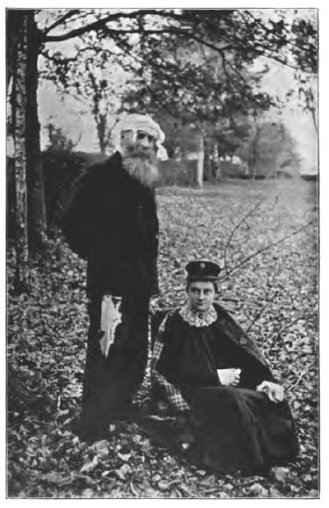

To the writer, recalling the hours that followed, indelibly imprinted on the mind as they must ever be, the fact that stands out the clearest was Bacon’s own absolute calmness and apparent perfect indifference to his fate. One thing alone seemed in the least to trouble him—the press telegram that he was writing to “The Times.” With the utmost care he composed his message, turned the sentences, counted the words, and copied them out on the forms. He was rather proud of what he had written, read it aloud for commendation, and was really genuinely distressed to think that Mr. Moberly Bell and his readers might not, after all, receive the benefit of it. Beyond this absurd and tiny detail the situation had no terrors for him, the near approach of death no fears. For himself he minded not at all, for his two younger companions he was all sympathy and consideration. The more desperate our circumstances grew, the more persistently cheerful he became. “If only we come out of this alive,” he said, “what friends we shall all be!”—this by way of cheering poor Mr. Spencer, thinking, as we knew, of his wife and little one at home, to whom, we believed, he wrote his farewell message. Breakfast was his next suggestion, and obediently we consumed an unappetizing meal. After this he proposed photography, and we unpacked the camera and snap-shotted the cloud floor, the sky, the open mouth of the balloon, and finally each other, huddled up in the corners of the car. The sun by this time was growing almost uncomfortably powerful, and to shield ourselves somewhat from his rays we tied scarves and coats about the ropes, and Bacon, since his cap was gone, improvised a head-covering from a pocket-handkerchief, the knotted ends of which hung in ridiculous fashion about his grey whiskers and patriarchal beard. In truth we were a forlorn crew, in a forlorn plight, and fairyland had proved a trap, and meteor hunting had brought us woe. Bacon waxed facetious at our rueful faces, and we had at least one hearty laugh over a situation that had comic as well as tragic sides to it.

For long we heard the sea beneath us (subsequent events led us to suppose we traversed some twenty miles of the Bristol Channel), but all the while from time to time arose sounds that made us believe we were still in the vicinity of some big sea-port town. We imagined it to be Bristol (though it may have been Cardiff), and we wondered if no help were to be had from all those thousands below, whose willingness to aid us we could not doubt, did they only know of our situation a couple of miles above them, behind the clouds. Suddenly we bethought us of the press telegraph forms with which Bacon’s pockets were filled. Why not use them as distress messages to the folk beneath, and get them to warn the coastguards round the neighbouring shores that we expected shortly to descend in the sea, so that they might be on the lookout and have their boats in readiness to pick us up if we came down in sight of land? It was the maddest of chances to rely on, of course, and the feeblest of straws to clutch at, but at least it was better than nothing. So out came pencil and forms, and, dividing the labour equally among us, during the next three hours we wrote and posted over the side three dozen or so neatly folded notes, labelled “Important,” and bearing the following message within :—

“Large balloon from Newbury overhead, above clouds. Cannot descend. Telegraph to sea coast (coastguards) to be ready to rescue.

“Bacon And Spencer, 11 a.m. Nov. 16.”

Surely their destination was the Bristol Channel, for two only were ever heard of again—picked up several days later on the Welsh mountains near Pontypridd, apparently many miles from where we threw them out.

Yet they served their purpose, if only in passing the time. They helped the hour of noon to come at last, and almost with the hour came our earliest ray of hope. Bacon, who kept watch over the aneroids, announced that we had fallen since the last reading from 9000 feet (our greatest height) to 7000, and were still falling. Nor was this all. Mr. Spencer, who had been gazing long and silently upon the cloud floor far below, suddenly exclaimed, “I can see a church!” It seemed impossible to suppose he could really have seen anything of the sort, and I knew from the soothing way in which my father laid a hand upon his shoulder and said, “Where, my good fellow, where? ” that he thought the long strain and hot sun had affected our aeronaut’s head, and that he was wandering. But, looking down also, we saw to our surprise that the cloud floor was thinning beneath us, as snow melting in the sunbeams, and actually breaking in places into pits and hollows, through one of which we caught a momentary glimpse of a white thread on a pink ground. The thread we knew for a road, and red soil belongs to the West of England. Land and not sea was still beneath us, but the next glimpse showed us our pace was quickening, and we wondered if we should yet reach the ocean before our voyage was at an end.

How slowly our balloon, dying obstinately by inches, crept down the sky, falling a hundred feet, stopping altogether, and then retrograding ninety-five. How fast and faster sped the earth beneath, seen in momentary peeps among the rolling vapour. For two long hours more—the most trying of our ten-hour voyage—the race continued, and then, at length, when nerves were strained near to breaking point, the mists once more received us, enveloped us but for a few minutes, and then let us through again beneath. Sea was before us and not far distant, but we heeded it not, since we were falling, now with great rapidity, on peaceful green fields below. The earth was rushing up towards us at a great rate, but not for the world would we risk, by the discharge of a grain more ballast than was necessary, a return to those wearisome realms aloft. With bent knees we awaited the shock of the fall, but when it came it proved infinitely more violent than we had anticipated. We had not reckoned indeed upon a boisterous gale of wind raging for several days past upon the Glamorganshire coast. But as we swooped downwards a sudden wild gust, sweeping from between the hills, caught our crippled craft, and sported with it in rudest horse-play. First it hurled us to earth with a crash that strained our groaning wicker basket in every twig and broke my right arm above the wrist. Next it dashed us, all sideways, in maddest steeplechase across the sloping gully in which we fell, our grapnel bounding impotently and furrowing long tracks in the grass behind. An eight-stranded barbed-wire fence was our first obstacle ahead, and a murderous one it looked. “Duck down in the basket!” cried Mr. Spencer, and we ducked low as the wires snapped and coiled about our shoulders. But one strand went over the top of the car, and I heard my father cry: “I am badly torn in the leg!” Of course I promptly pictured him as bleeding to death, but there was no time to investigate the damage, for the next instant, with a crash and lashing of leafless branches, we were in the top of a weather-beaten oak tree, and the moment later we had carried the whole top away in our rigging and were rolling with the big torn branches among gorse bushes in the next field. The silk was flapping and tearing in, the gale with a noise like thunder, but in the root of the splintered oak the anchor held, and our course was stayed.

Soon in the distance came the sound of excited voices, calling to each other, but in an unknown tongue, and a little group of dark-eyed men came panting up, but halted at a respectable distance from the struggling, tossing monster. “Come and help us!” shouted my father; then as they still did not move: “Come and help, you fools! Don’t stand gaping there!” But never before in the memory of man had so strange an object fallen from a cloudy sky on the outskirts of the town of Neath, and for a few moments longer the cautious Welshmen refused to approach. The hurried arrival of the landowner and neighbouring residents, however, soon inspired them with confidence, and never surely was a more hospitable welcome accorded to wayworn travellers. It was half-past two when we stepped at length from our basket world upon terra firma, after what Mr. Spencer declared was the roughest landing of all his long experience. Our voyage then had lasted for ten hours, and terminated but a mile and a half from the sea, towards which we were directly heading when we fell. Five minutes more, therefore, would have seen us over the Atlantic, wildly rough, so we learned, at the time. So long and perilous a voyage constituted an undoubted record for ballooning in the British Islands, for danger and for length of time aloft. Early next morning a happy, but utterly disreputable-looking, pair presented themselves proudly at Printing House Square; the writer with bandaged arm in sling, Bacon in borrowed hat and borrowed trousers—his own nether garments were torn completely to rags—the back of his coat one plaster of mud which he absolutely refused to have brushed away. I think the editorial staff were a little impressed with our appearance; certainly the interview was gratifying and flattering. Out in the streets our exploit was already on posters and headlines, passers identified us, policemen grinned recognition. For days the papers were full of the adventure, and, Silas Wegg like, the “Globe” dropped into poetry and perpetrated a verse described as the composition of “a humble Cockney acquaintance”:—

“I’m thinkin’ no rasher excursion’s been tiken’

Than that Meteor hunt by balloon of old Bicon.

As it dived towards the earth, getting nigher an’ nigher,

I reckon he thought, “Ere’s the fat in the fire!’

And when he got chucked, an’ lay battered an’ shiken,

I bet that he felt just a bit afride Bicon!”